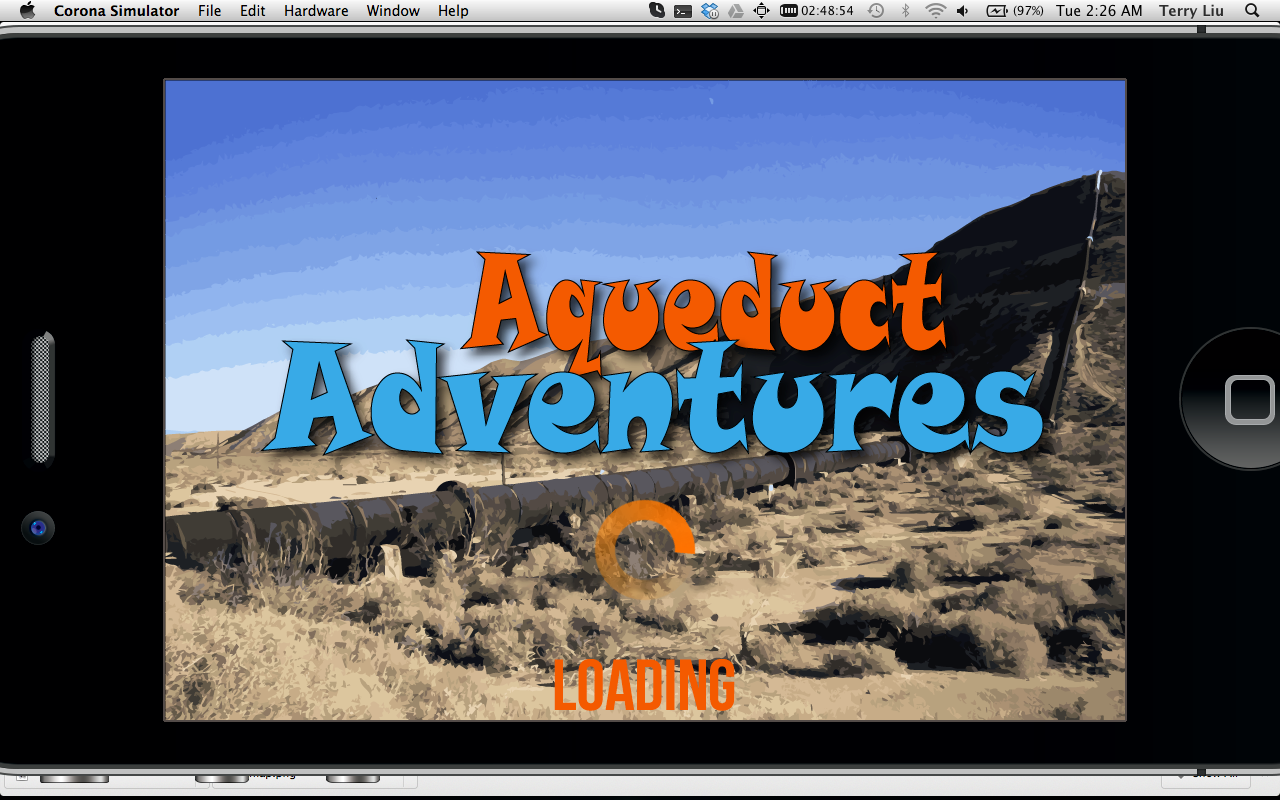

Aqueduct Adventures

This project was the result of course “CS 470 - Game Development”, which was one of the most rewarding classes I have ever taken as it taught me a surprising amount about what it takes to build a product end-to-end.

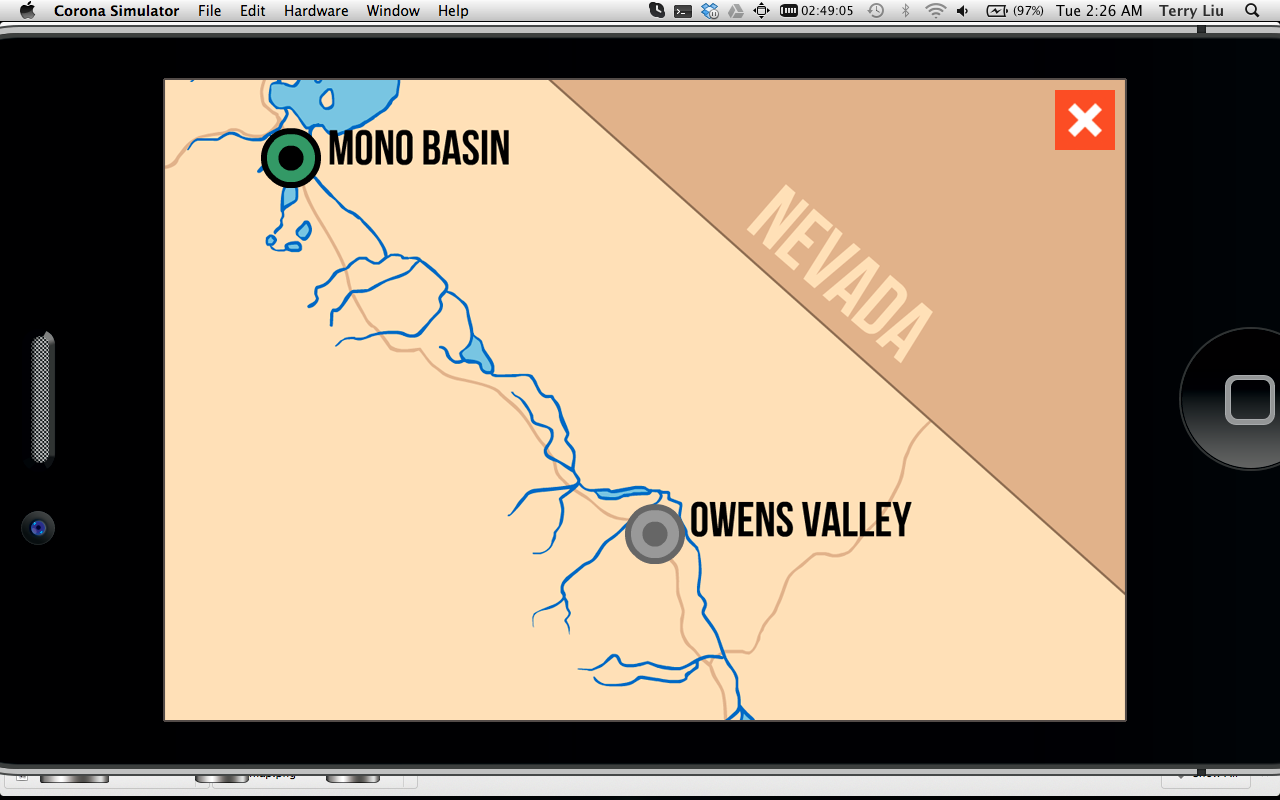

Aside from the constraints of the technology to develop on (Corona SDK, Box2D, Lua) and what the game’s underlying theme should be about (the LA Aqueduct), we were given full autonomy. We had to come up with the game concept, designs, gameplay mechanics, graphics, audio, code, etc. Over the span of a single quarter (10 weeks), my team and I collectively spent hundreds of hours outside of class to build a fully functional prototype for the Android platform using technology that was completely new to us.

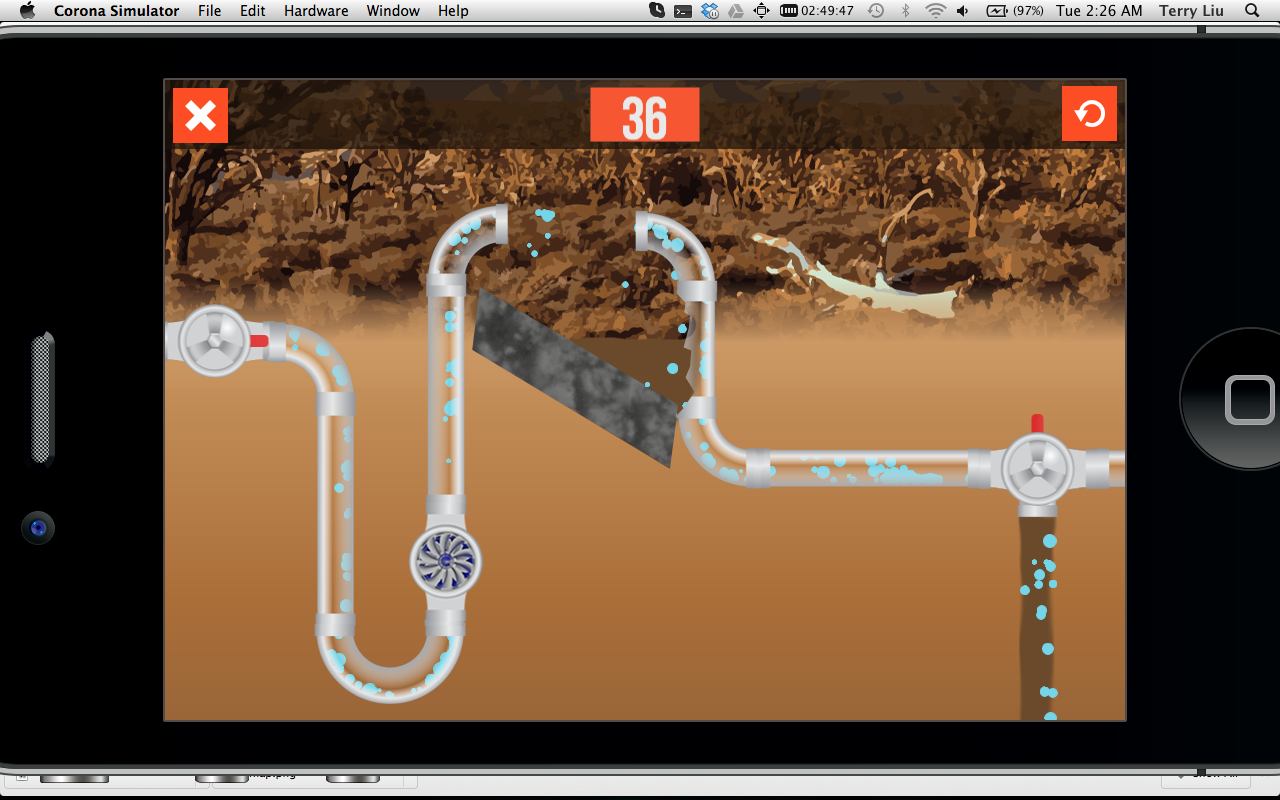

The object of our puzzle-type game was simple: manage the flow of water and retain as much as possible. If enough water made it in time to the reservoir at the end of a level, you would advance to the next level.

I was personally responsible for two breakthroughs that I am particularly proud of even to this day as they required a level of open-ended creative problem-solving that was rarely called upon in other classes.

One of our first challenges was determining how to simulate water flow, a slippery task (pun intended). We decided to use many small “particles” of water that would flow from a starting reservoir tank to an ending one, and early testing gave us confidence that the effect was convincing enough. However, when we increased the amount of water in the first level of the game, it became apparent that things were extremely computationally expensive. Every time we loaded the level, all the water “particles” in the starting reservoir would bounce against each other and cause a rippling effect of interactions that quickly compounded and slowed performance to an unresponsive crawl. Things would improve as the water spread out while progressing through the level, but the same issue occurred again at the end of the level when the water accumulated in the ending reservoir.

We brainstormed and researched some clever but overly sophisticated ways of making the water more of an amorphous “blob” with fewer particles to reduce interactions, but there was no clear path to implementation, and we were pressed for time. Eventually, I realized that our product was a game, not a real-life simulation. We could simply generate the water particles on-the-fly from the starting valve and have them disappear from the game environment as soon as they reached the end reservoir. This felt no different to the player, as the perception of what was happening remained virtually the same, and yet it drastically reduced the number of water “particle” interactions, allowing our game to run incredibly smoothly. This major breakthrough actually helped in a number of other ways as well; it sped up the testing process since the app would no longer stall in performance and it also simplified things like state management and win condition logic.

The second breakthrough came as we got into more advanced level design. To increase the degree of challenge and make use of more screen real estate, we had to introduce turns in the water pipes. Up to that point we had only experimented with straight lines as physical boundaries for the water to travel along and that was as simple as drawing a line with some coordinates:

function PhysicsLineFactoryII:makePhysicsLine(x0,y0,x1,y1,tag)

That meant drawing vertical and horizontal pipes with a given width and height was also easy:

function PhysicsLineFactoryII:makeHorizPipeLine(x,y,w,h,tag)

self:makePhysicsLine(x,y,x+w,y,tag);

self:makePhysicsLine(x,y+h,x+w,y+h,tag);

end;

function PhysicsLineFactoryII:makeVertPipeLine(x,y,w,h,tag)

self:makePhysicsLine(x,y,x,y+h,tag);

self:makePhysicsLine(x+w,y,x+w,y+h,tag);

end;

T-shaped pipes that intersected horizontal and vertical pipes were a little trickier and also required an orientation specification. I used compass directions at the time although in hindsight, perhaps “top”, “bottom”, “left”, “right” might have been more sensible:

function PhysicsLineFactoryII:makeNorthTPipe(x,y,w,h,tag)

self:makePhysicsLine(x,y,x,y+h,tag);

self:makePhysicsLine(x+w,y,x+w,y+h,tag);

self:makePhysicsLine(x-w,y+h,x,y+h,tag);

self:makePhysicsLine(x+2*w,y+h,x+w,y+h,tag);

self:makePhysicsLine(x-w,y+2*h,x+2*w,y+2*h,tag);

end;

function PhysicsLineFactoryII:makeSouthTPipe(x,y,w,h,tag)

...

function PhysicsLineFactoryII:makeWestTPipe(x,y,w,h,tag)

...

function PhysicsLineFactoryII:makeEastTPipe(x,y,w,h,tag)

...

The real challenge was in figuring out how to draw the curves needed for turns in the pipe. The first solution we tried was a library package that could draw arcs but it gave very limited control over the exact shape and orientation. It was only able to draw simple elliptical arcs connecting two points and this caused numerous issues in the game environment. Not only did it take excessive time to position the arcs, their poor fitment meant that they would often either leave gaps so that water particles would leak out of the pipe system or they would protrude at attachment junctures and impede the flow of water unintentionally.

We needed a way to maintain a constant pipe width through the turn while also leaving it easy to

configure the turn radius, pipe girth, and pipe placement. It also had to connect seamlessly with

other pipe segments so that no unwanted leaks or blockages would be introduced. I distinctly

remember whiteboarding late into the night in my room to solve our digital plumbing issue. The key

insight was realizing that two straight lines forming a \/ shape is kind of just a really badly

drawn semi-circle. Three straight lines, |_|, is better but still bad. Extending this principle

with a few more drawings using even more line segments, I was soon convinced that a reasonably

smooth semi-circle was feasible if enough line segments were used.

I spent the remainder of that evening using geometry to derive the algorithm that would allow us to much more easily implement our precise pipe turns. I tested various counts of line segments up to 12 but realized that the difference was not really discernable beyond 8 segments. Once I had the ability to make any quarter-circle turn, any semi-circle turn could be formed by combining two quarter turns and the rest was as easy as pie (no pun intended).

Looking back now, this code could almost certainly have been further refactored, less hard-coded, etc. but we knew we weren’t going to revisit this logic much at all once it was working so we moved on to actual level building. This breakthrough and algorithm was key to actually enabling us to produce pipe layouts and levels at a sustainable pace to complete the project and it also served to remove some buggy interactions from our gameplay.

We aced the project and final presentation and it was a good lesson in how realistic projects with deadlines can make you reprioritize what code quality means – done well enough early is often better than done perfectly later.

-- y is inverted

-- r is the radius of the turn, not the pipe dimensions

function PhysicsLineFactoryII:makeNECurvePipe(x, y, r, g, tag)

-- Using 8 line segments; can use more if needed

-- Connects 9 points using circular intersections

-- divided by 5 in both x and y directions

local d = r / 5;

local y1 = y - math.sqrt(r^2 - (1*d)^2);

local y2 = y - math.sqrt(r^2 - (2*d)^2);

local y3 = y - math.sqrt(r^2 - (3*d)^2);

local y4 = y - math.sqrt(r^2 - (4*d)^2);

local y5 = y - math.sqrt(r^2 - (5*d)^2);

local x6 = x + math.sqrt(r^2 - (3*d)^2);

local x7 = x + math.sqrt(r^2 - (2*d)^2);

local x8 = x + math.sqrt(r^2 - (1*d)^2);

-- Outside curve

cst = {

{ x, y-r, x+1*d, y1, },

{ x+1*d, y1, x+2*d, y2, },

{ x+2*d, y2, x+3*d, y3, },

{ x+3*d, y3, x+4*d, y4, },

{ x+4*d, y4, x6, y-3*d, },

{ x6, y-3*d, x7, y-2*d, },

{ x7, y-2*d, x8, y-1*d, },

{ x8, y-1*d, x+r, y, },

};

for j=1,#cst do

local sh = cst[j];

self:makePhysicsLine(sh[1],sh[2],sh[3],sh[4],tag);

end

-- g is girth of the pipe itself

r = r - g;

d = r / 5;

local y1 = y - math.sqrt(r^2 - (1*d)^2);

local y2 = y - math.sqrt(r^2 - (2*d)^2);

local y3 = y - math.sqrt(r^2 - (3*d)^2);

local y4 = y - math.sqrt(r^2 - (4*d)^2);

local y5 = y - math.sqrt(r^2 - (5*d)^2);

local x6 = x + math.sqrt(r^2 - (3*d)^2);

local x7 = x + math.sqrt(r^2 - (2*d)^2);

local x8 = x + math.sqrt(r^2 - (1*d)^2);

-- Inside curve

cst = {

{ x, y-r, x+1*d, y1, },

{ x+1*d, y1, x+2*d, y2, },

{ x+2*d, y2, x+3*d, y3, },

{ x+3*d, y3, x+4*d, y4, },

{ x+4*d, y4, x6, y-3*d, },

{ x6, y-3*d, x7, y-2*d, },

{ x7, y-2*d, x8, y-1*d, },

{ x8, y-1*d, x+r, y, },

};

for j=1,#cst do

local sh = cst[j];

self:makePhysicsLine(sh[1],sh[2],sh[3],sh[4],tag);

end

end;

function PhysicsLineFactoryII:makeNWCurvePipe(x, y, r, g, tag)

...

function PhysicsLineFactoryII:makeSWCurvePipe(x, y, r, g, tag)

...

function PhysicsLineFactoryII:makeSECurvePipe(x, y, r, g, tag)

...

function PhysicsLineFactoryII:makeSouthHorseshoePipe(x, y, r, g, tag)

local offset = 2;

self:makeSECurvePipe(x - offset, y, r, g, tag);

self:makeSWCurvePipe(x, y, r, g, tag);

end;

function PhysicsLineFactoryII:makeNorthHorseshoePipe(x, y, r, g, tag)

...

function PhysicsLineFactoryII:makeEastHorseshoePipe(x, y, r, g, tag)

...

function PhysicsLineFactoryII:makeWestHorseshoePipe(x, y, r, g, tag)

...