Bonsai Metric Tree

This project spanned mid to late 2020 and was another idea initially dreamt up by Jay Garg.

By this point in our careers we had both seen project planning done in a number of ways and the common denominator was that they all seemed insufficient. There was a lack of precision, adaptability, and detail in most planning processes, and we set out to solve this.

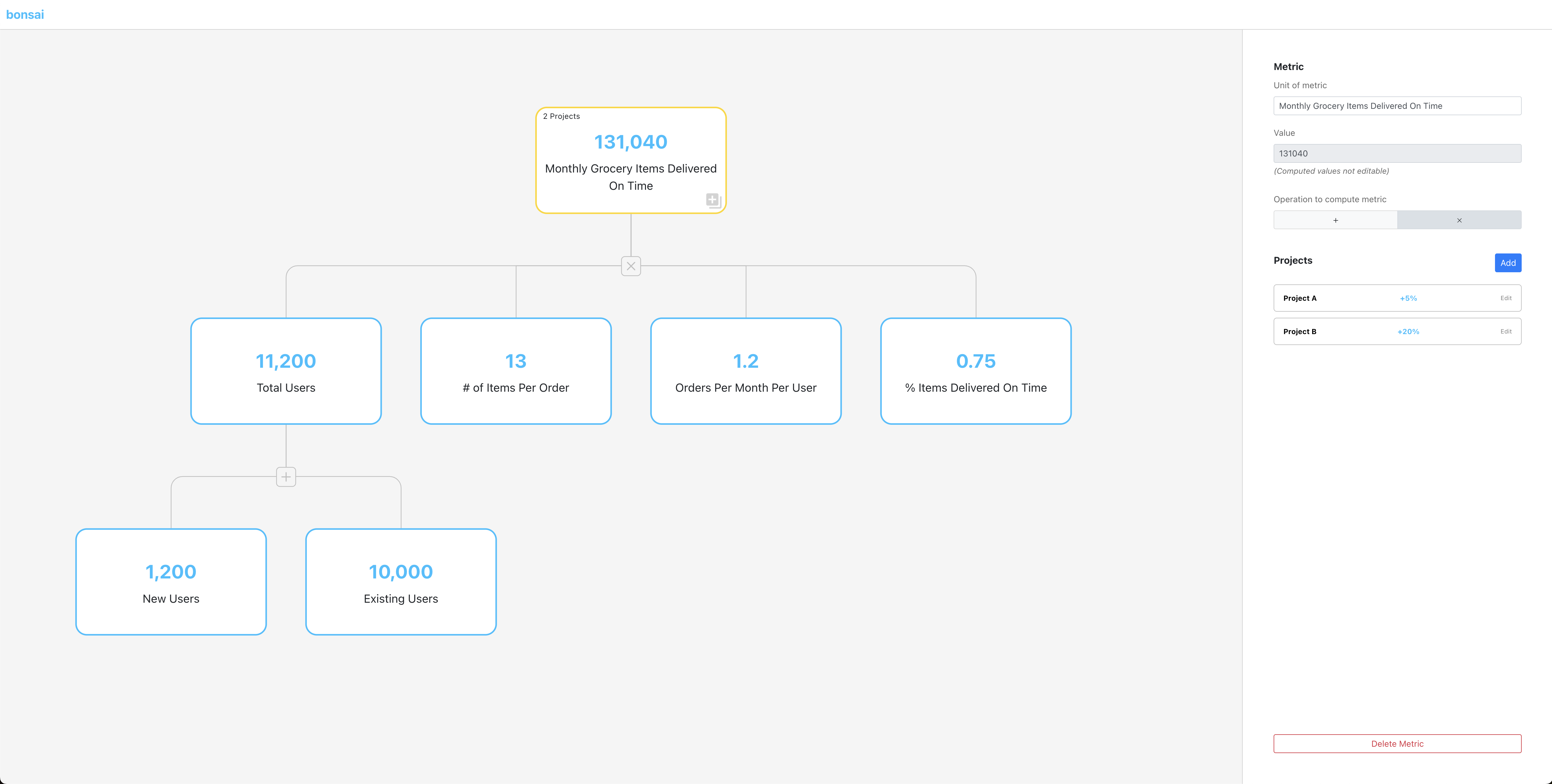

“Bonsai” was born shortly after as we imagined a “metric tree” that would enable you to break down anything into its more basic components so that you could estimate those simpler components and have it compute the final top-level result. You can’t improve something that you can’t measure, and almost anything worth solving can be measured in some way. The easiest things to measure or estimate are typically simpler and at the bottom of the tree you’re thinking about. Based on these assumptions, we solved for precision by making everything about numbers, specifically the low-level numbers or the “leaves” of the tree.

We solved for adaptability by making it so that you could add a new leaf node anywhere or change any values at any time. Once you did that, the tree would be recomputed where necessary to reflect the new values. Plans change all the time and this was our way to ensure that we can always adjust our understanding of the metrics based on new estimates or insights.

To add an extra level of detail, we had planned to solve for cases where a number of projects could affect any number of nodes outcomes. For example, you could define a project “A” that affects node 1 by 10% and node 2 by 5% and a project “B” that affects node 3 by 20%. If your team could only choose one project to do between the two of them, being able to see the final outcome for either project would make for a quick comparison and decision. Of course, all of this is assuming that your baseline estimates and percentages of impact are correct in the first place, which becomes the new challenge. As tough as those details are to get right, we found it preferable to sticking a wet finger in the air and saying, “I think the wind is blowing this way…”

Here is what the prototype ended up looking like:

As we began exploring how we could build such a thing, it quickly became clear where the major obstacles would be. Spoiler alert: the tree (duh). The nodes were going to be relatively simple React components. We determined that we could have a single node be considered “active” at any time and have that node’s configuration open for editing in the side panel. Simple enough. We soon realized, however, that we didn’t have the slightest clue about how to render a tree of said nodes, never mind dynamically reshaping all of it on the fly. By “reshaping”, we mean automatically repositioning all the nodes of the tree. This was critical for us, as we saw little value in a tool that would require manual repositioning each time a change disrupted the balance or visual spacing of the tree.

We had scoured the web at the time for a pre-made solution that would get us at least partway there, because we knew it wasn’t going to be trivial to build. Nothing really fit what we needed though. The closest we got were solutions that provided a dynamic tree with extremely limited ability to adapt what was in each node. As tempting as those solutions were at first, early testing convinced me that trying to repurpose them for our use-case was going to be even more frustrating and time-consuming than figuring out how to build our own in the long run.

Despite not having any leads at the time, we made the hard decision to focus intently back on how we would solve it if forced, and we revisited our problem with fresh eyes. It’s amazing sometimes what you find or what you become capable of when there are no other options. I couldn’t believe it when I found this paper called A Node-Positioning Algorithm for General Trees written by John Q. Walker II. As you can probably tell from the title, it was exactly what we needed (at least on paper), and all I had to do was adapt our own algorithm from it – easier said than done.

It took several nights of hard work but I did successfully adapt the algorithm for our purposes, and that was ultimately what powered our ability to reshape our trees automatically. Here it is in action:

SVG Paths were what enabled us to draw precise lines connecting the tree nodes once they were

positioned. Looking back now, I’m a little surprised that all of the line-drawing is handled by less

than 200 tidy lines of code (including two React components’ worth of boilerplate). Then again, it

was mostly just lightweight math wrapped around the svg and path elements. The real test here

was learning what was even possible with HTML and SVG in the first place: as it turns out, quite a

bit! Enabling the rounded corners for paths leading to edge nodes was the final cherry on top.

The rest of the tech stack was kept fairly simple as our main goal was to launch a proof of concept, so we used Django, Python, React, Docker, and GCP. Once we had the rendering and repositioning working, we quickly added in other features like the ability to set a mathematical operator for a parent node so that it knew how to auto-calculate its own value by applying that operator on the values of its children. It was around this time that I was reminded of the perils of floating point arithmetic.

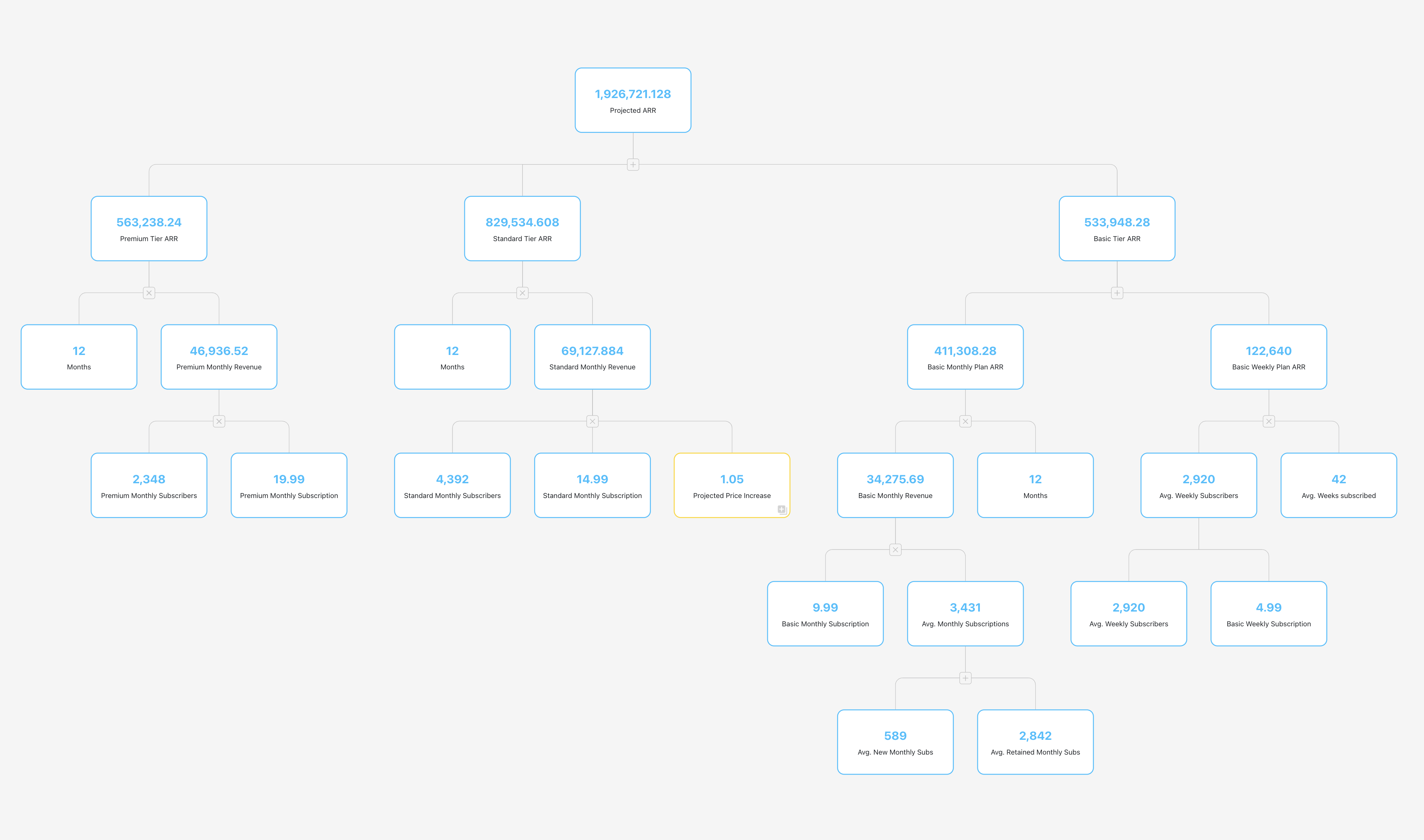

We finally had our “metric tree” tool and it seemed like it could be generalized for a variety of uses so we shared it around. Here is a slightly more complex example showing how it might have been used to model annual recurring revenue (ARR) for a product with different subscription tiers:

In the end, we didn’t garner enough attention or see enough usage from any end-user candidates to suggest that it was worth pursuing, but it was clear that we were learning from our earlier mistakes. While it took us years to recognize a failure to launch previously, it took us only months to both build and draw similar conclusions with this project. In that time, we had also built something much less broad but in many ways far more complex and unique than what we had built before, which was a good place to be for prototyping.

I am currently seeking approval from the copyright owner(s) to apply an MIT license to this work such that it can be used freely. Regardless, the source code for the core logic behind our tree positioning package has since been made public on GitHub, and it will proudly carry the name of this original project forward. You can check it out at Bonsai!